Asynchronous Execution

Summary

Asynchronous Execution is a technique that allows Monad to substantially increase execution throughput by decoupling consensus from execution.

Decoupling consensus from execution allows Monad to substantially increase the execution budget, since execution goes from occupying a small fraction of the block time to occupying the full block time.

Background: interleaved execution is inefficient

Consensus is the process where nodes come to agreement about the official ordering of transactions. Execution is the process of actually executing those transactions and updating the state.

In Ethereum and most other blockchains, execution is a prerequisite to consensus. When nodes come to consensus on a block, they are agreeing on both (1) the list of transactions in the block, and (2) the merkle root summarizing all of the state after executing that list of transactions. As a result, the leader must execute all of the transactions in the proposed block before sharing the proposal, and the validating nodes must execute those transactions before responding with a vote.

We refer to this style of blockchain as one that has execution interleaved with consensus. In this paradigm, the time budget for execution is extremely limited, since it has to happen twice and leave enough time for multiple rounds of cross-globe communication for consensus.

Additionally, since execution will block consensus, the per-block gas limit must be chosen extremely conservatively to ensure that the computation completes on all nodes within the budget even in the worst-case scenario.

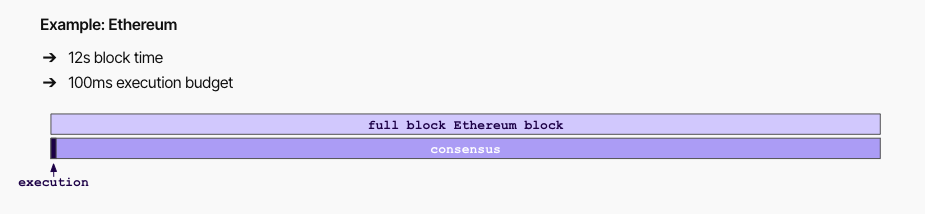

The result is that the per-block gas limit is a tiny fraction of the block time. In particular, in Ethereum, the gas limit (30M worst-case gas) corresponds to a roughly 100ms time budget, even though the the block time is 12 seconds:

Comparing Ethereum execution budget to block time

That's 1% of the block time! In short, interleaving consensus and execution has a massive time-shrinking effect.

What if it didn't have to be this way?

Asynchronous Execution

Monad decouples consensus from execution, moving execution out of the hot path of consensus into a separate, slightly-lagged swim lane.

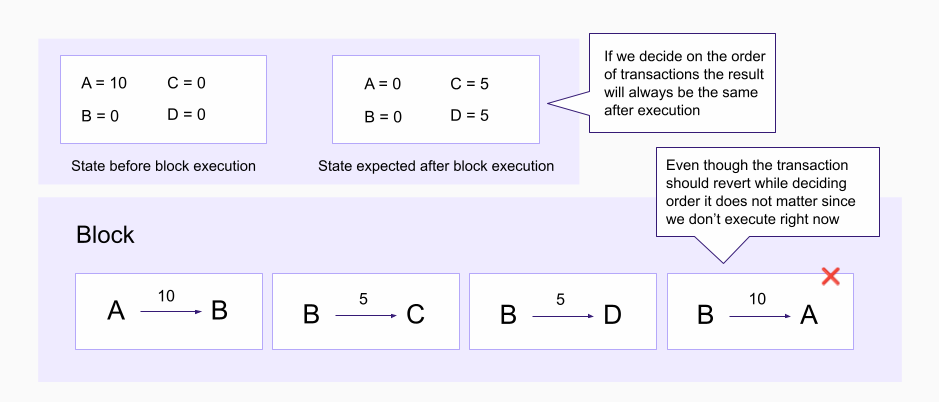

In Monad, nodes come to consensus (i.e. agreement about the official ordering of transactions), without ever executing those transactions.

That is, the leader proposes an ordering without knowing the resultant state root, and the validating nodes vote on block validity without knowing (for example) whether all of the transactions in the block execute without reverting.

When a block is finalized, every node in the network (validators and full nodes) can execute the block's transactions to produce the latest, agreed-upon state.

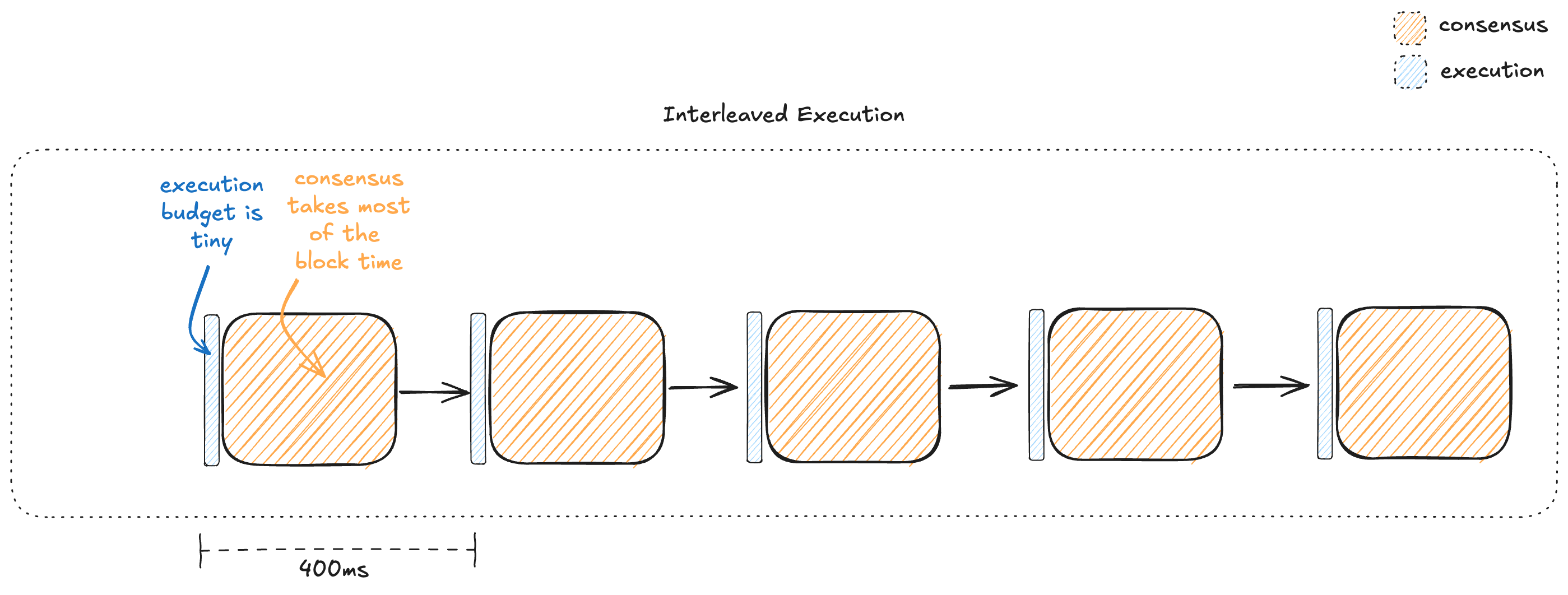

As a result of this change, execution can be budgeted the full block time. To see why, consider the somewhat stylized diagrams, in which blue rectangles correspond to execution, and orange rectangles correspond to consensus:

Interleaved execution

In interleaved execution, the sum of the execution and consensus budgets equals the block time, and consensus occupies most of the block time.

Interleaved execution

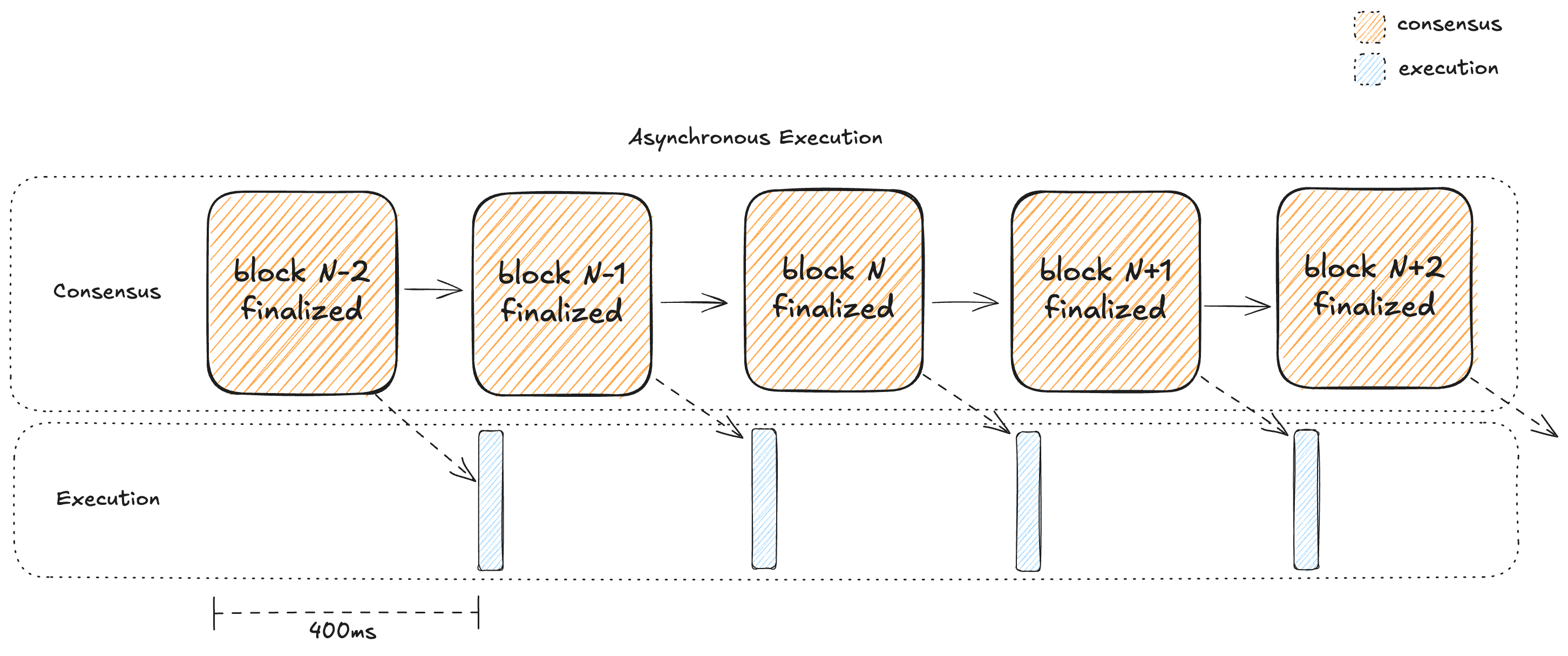

Asynchronous execution

In asynchronous execution, consensus occupies the full block time - and so does execution, because they are occurring in separate swim lanes, at the same time:

Asynchronous execution

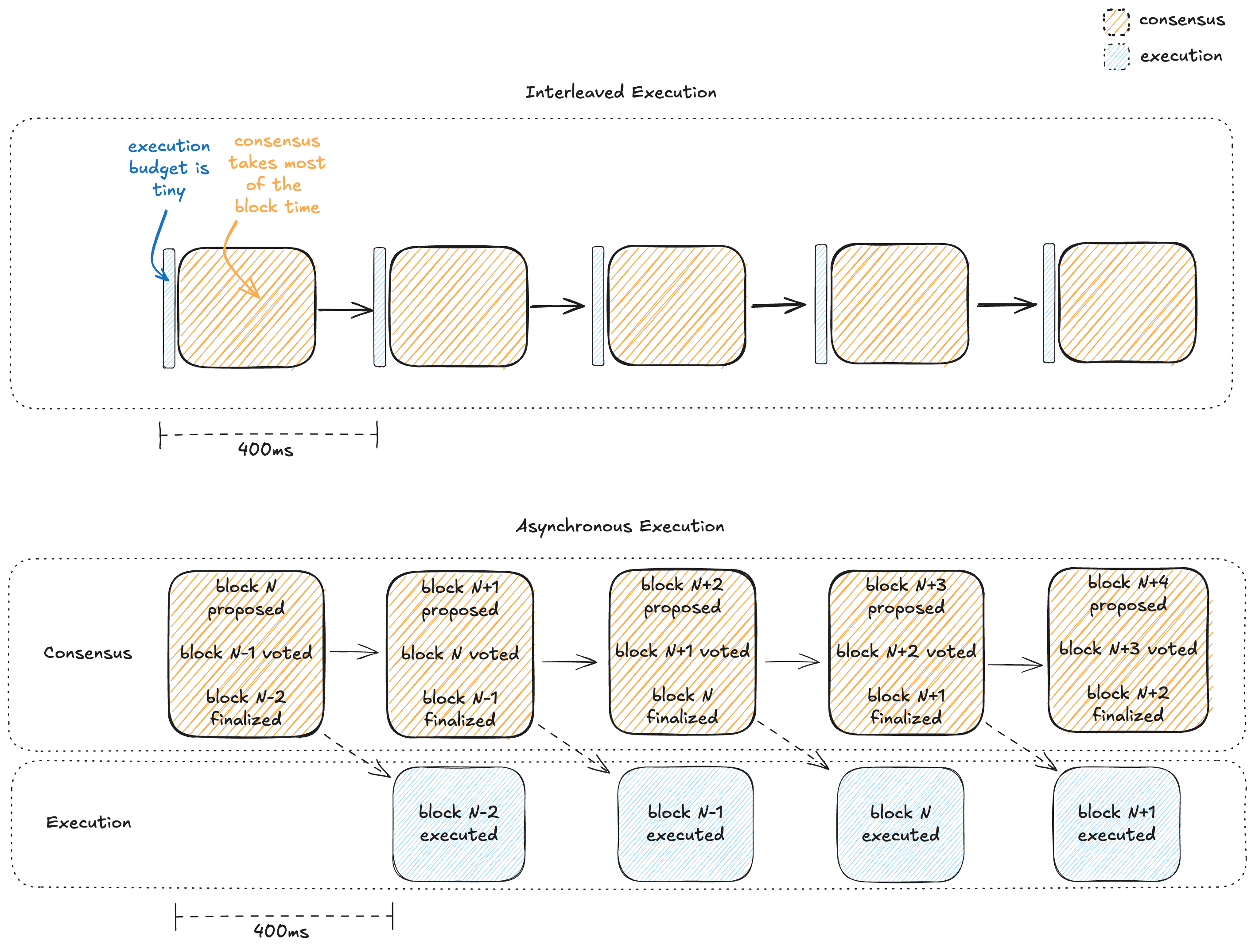

Comparison

Comparing the two styles side by side, you can see the benefit of the asynchronous style: the execution budget can be significantly expanded to occupy the full block time:

Top: interleaved; bottom: asynchronous.

Determined ordering implies state determinism

Although execution lags consensus, the true state of the world is determined as soon as the ordering is determined. Execution is required to unveil the truth, but the truth is already determined.

It's worth noting that in Monad, like in Ethereum, it is fine for transactions in a block to "fail" in the sense that the intuitive outcome did not succeed.(For example, there could be a transaction included in a block in which Bob tries to send 10 tokens to Alice but only has 1 token in his account. The transfer 'fails' but the transaction is still valid.

The outcome of any transaction, including failure, is deterministic.

Example of transaction determinism even when some transactions fail

Finer details

Delayed Merkle Root

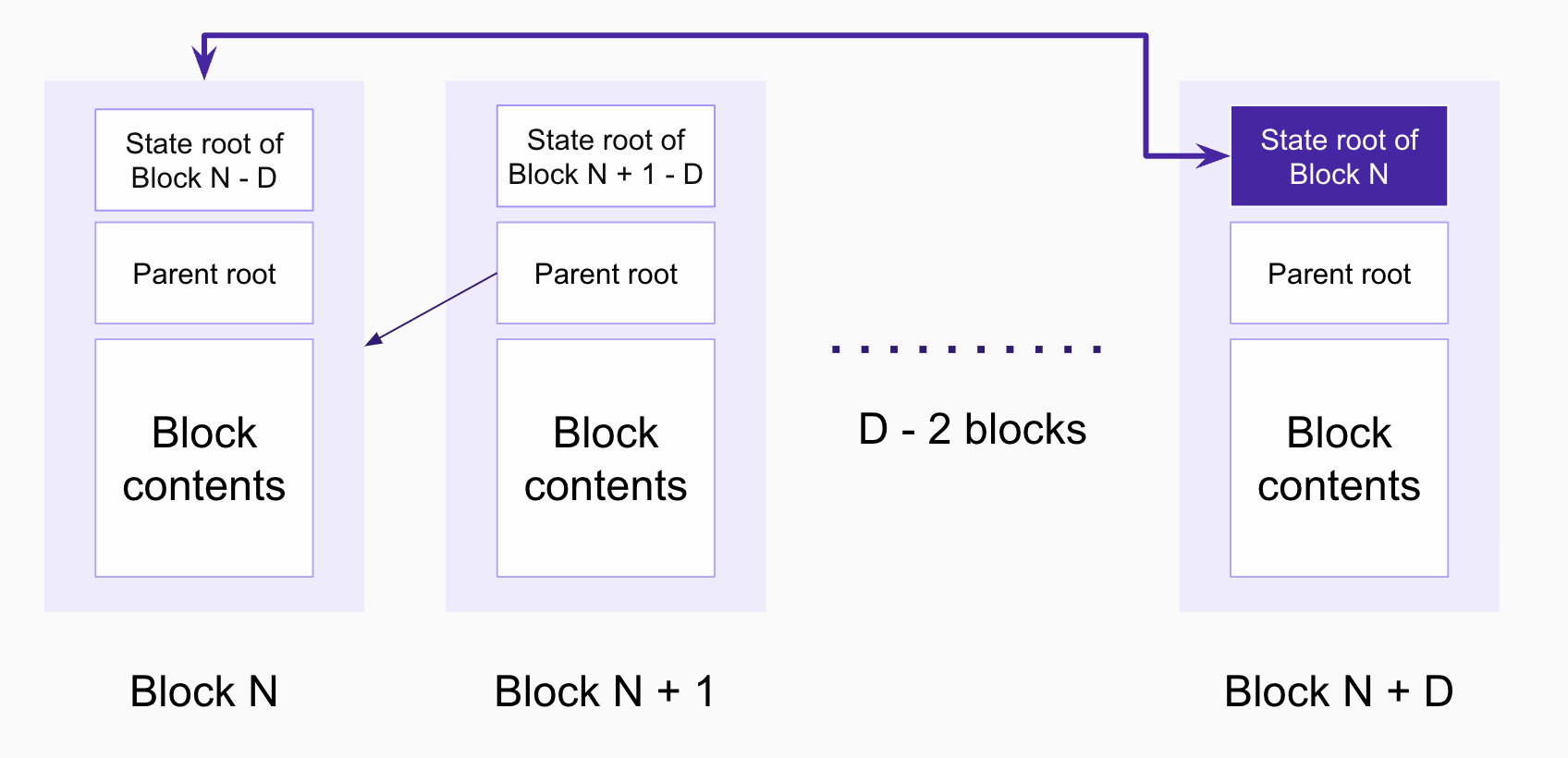

As mentioned above, Monad block proposals don't include the merkle root of the state trie, since that would require execution to have already completed.

All nodes should stay in sync because they're all doing the same work. But it'd be nice to be sure! As a precaution, proposals also includes a merkle root from D blocks ago, allowing nodes to detect if they're diverging. D is a systemwide parameter (currently set in testnet and mainnet to 3).

Delayed merkle root validity is part of block validity, so if the leader proposes a block but the delayed merkle root is wrong, the block will be rejected.

As a result of this delayed merkle root:

- After the network comes to consensus (2/3 majority vote) on block

N(typically upon receiving blockN+2, which contains a QC-on-QC for blockN), it means that the network has agreed that the official consequence of blockN-Dis a state rooted in merkle rootM. Light clients can then query full nodes for merkle proofs of state variable values at blockN-D. - Any node with an error in execution at block

N-Dwill fall out of consensus starting at blockN. This will trigger a rollback on that node to the end state of blockN-D-1, followed by re-execution of the transactions in blockN-D(hopefully resulting in the merkle root matching), followed by re-execution of the transactions in blockN-D+1,N-D+2, etc.

Ethereum's approach uses consensus to enforce state machine replication in a very strict way: after nodes come to consensus, we know that the supermajority agrees about the official ordering and the state resulting from that ordering. However, this strictness comes at great cost because interleaved execution limits execution throughput. Asynchronous execution achieves state machine replication without this limitation, and the delayed merkle root serves an additional precaution.

Delayed merkle root

Reserve balance

Because consensus can only be assumed to have up to the D-block delayed view of the global

state, it is necessary to adjust the consensus and execution rules slightly to allow consensus to

safely build blocks that include only transactions whose gas costs can be paid for.

Monad introduces the Reserve Balance rules to ensure this. The rules place light restrictions on when transactions can be included at consensus time, and imposes some conditions under which transactions will revert at execution time.

Speculative execution

In MonadBFT, nodes receive a proposed block N at slot N, but it is not finalized until slot N+2. During the intervening time, a node can still locally execute the proposed block (without the guarantee that it will become voted or finalized). This allows a few nice properties:

- In the likely event that the proposed block is finalized, the validator node has already done the work and can immediately update its merkle root pointer to the result.

- Transactions can be simulated (in

eth_calloreth_estimateGas) against the speculative state which is likely more up-to-date.

Transactions from newly-funded accounts

Because consensus runs slightly ahead of execution, newly-funded accounts which previously had zero balance cannot send transactions until the transfer that credits them with tokens is D blocks old.

In practice, this means that if you send tokens from account A into an account B (which has 0 balance), then you should wait until seeing the transaction receipt (indicative that that block has reached Finalized state), and then wait another 0.4 seconds.

Alternatively, depending on the nature of intended transaction from B, it may be possible to write a smart contract callable by A which combines the funding operation and whatever B was intending to do, requiring no delay between funding and spending.

Block states

See block states for a summary of the states through which each block progresses.